DOES SIZE MATTER?

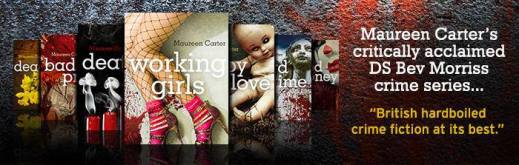

Six years ago I was asked to contribute a short story to an anthology of crime fiction. The book would be sold in aid of charity and my then publisher thought it would be a good opportunity to showcase my series detective. Helping cancer research and introducing DS Bev Morriss to a wider audience? What’s not to like? I jumped at the chance.

I’d also add that having written five books in the series by then, coming up with a short story didn’t strike me as a big ask.

Don’t shoot me down in flames. I’m not suggesting for a second that short stories are easy to write. In some ways, they need similar discipline and focus as full-length fiction. But, for me, novels are long haul not short hop. I find working on them more demanding and considerably more difficult. They need a different approach, and I have to make a bigger commitment – many months not several days.

Not everyone sees it that way. I once had a heated debate with a woman who was absolutely adamant that short stories were harder to write and needed more skill and imagination from the author. Nothing I said budged her opinion an iota. How much experience did she have, I hear you ask? She’d not produced a word of fiction in her life. I shrugged mental shoulders and moved on. Each to their own – that’s fine by me.

The anthology’s available via Amazon and here’s my offering, should you wish to read it. Before The Fall is still the only short fiction in which Bev appears. Maybe I should rename it, Morriss Minor?

BEFORE THE FALL

‘Thank God you’re here, sarge. He’s threatening to jump.’

A line of sweat glistened above the young officer’s lean top lip; his voice held an uncharacteristic catch. Detective Sergeant Bev Morriss divined the signs. For rookie PC Daniel Rees this was a first: pavement huggers as they’re known in the trade.

‘Over my dead body,’ she muttered. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder on a patch of slightly tacky tarmac. Squinting against the fierce midday sun, Bev’s gaze followed the none-too-steady line of Rees’s finger. Her strikingly blue eyes put the azure sky in the shade. Not that she was aware of that – she’d blanked everything bar the young man hunkered on a flat roof four floors up, trainers just jutting over the edge.

‘What d’we know, Danny?’

‘Not a lot.’ Rees turned his mouth down. ‘Says he’ll take a dive if anyone goes near. He was chucking bricks a minute ago.’

Hand shielding her eyes, Bev focused on the hunched figure. Playing in her head were various ways the incident could pan out. ‘How long’s he been up there?’ She caught her breath surreptitiously. The sprint from the hastily abandoned police motor now straddling a near-distance kerb, had led her to make a mental note or three: join a gym, re-join old gym, attend any gym. Rees was fitter than a surfing whippet.

‘Not had time to ask around yet, sarge.’ The hankie he dabbed round his neck was already damp. Summer in the second city. Constable Rees – tall and dark – was losing his cool. ‘We got the call-out ten-twelve minutes back.’

She nodded, knew that the ‘we’ included fire and ambulance crews on standby down the road. She’d clocked them as she cruised past looking for a space. The alert had gone out over the police radio, Bev happened to be in the vicinity, offered to take a look. Her partner Mac Tyler was hooking up, soon as. The turnout might be over-kill but, better safe . . .

It wouldn’t be pretty if Batboy spread his non-existent wings. The mean-looking pebbledash structure wasn’t one of Small Heath’s poxy high rises, but taking four floors without a lift wasn’t a good move.

‘One of this lot might know something.’ Rees jabbed a thumb over his epaulette. Gawpers were gathering behind a police cordon that was still being erected round the ugly squat block. Bev presumed the defunct building had housed council offices, tenant support, something of that ilk. Whatever, the show was gratis and the audience was rapt.

‘Spectator sport, Danny.’ She delved in a voluminous bag for aviator shades. ‘Free fall . . . better than the Olympics.’

Sunglasses in situ, she checked out the crowd. Several faces and craned necks were vaguely familiar. The Coppice estate – known round Highgate nick as the cop-it – was little more than an annexe to Winson Green prison. She noted a couple of uniforms mingling with the jobless, feckless and, in at least two cases, legless voyeurs. The officers were jotting names, numbers, addresses, covering the basics. Anything earth-shattering would be filtered back pronto. Earth-shattering? Maybe not.

‘I reckon he wants his mam.’ The grating vocals emanated from behind. Bev and Rees whipped round so fast they almost collided. An old woman had slipped through the police tape and now stared skywards, scrawny arms folded tight across a faded Playgirl T-shirt. Her rust coloured perm framed a face like a sepia doily.

‘No worries. We can sort that . . . Mrs . . .?’ Bev paused but her prompt was ignored. The old dear hadn’t wrested her glassy-eyed gaze from the roof. Bev registered fluffy mauve slippers and thick Norah Batty tights. Wrinkles must live close by, probably one of Batboy’s neighbours, which meant a squad car could whisk the mother to the scene before you could say trained negotiator. Bev rubbed her hands. Sorted.

The old woman gave a derisive sniff. ‘She’s gone AWOL.’

Or maybe not. She stifled a sigh. ‘I’m DS Morriss. Bev Morriss.’ She flashed her trust-me-I’m-a-detective smile. ‘And you are . . .?’

‘Six kids. And she buggers off just like that.’ Fingers clicked like snapping twigs.

A tinny Green Sleeves issued from an ice cream van; frying-onion-odour wafted in the sultry air. Bev took a calming breath. ‘Look, love,’ she said, tapping the woman’s arm. ‘If you can just give us . . .’

‘Be with some bloke.’ Dazzling dentures had come adrift. A darting worm of a tongue nudged them back in line.

Bev’s fists were balled. The clock was ticking and the Jammy Dodger wannabe was still up there. ‘If you can just give us the boy’s name, love.’ Priority. Establish communication. Forge a rapport. Police procedure. Common sense, really.

‘Cheap tart.’ The old woman could’ve been talking to herself.

‘Enough already.’ Bev stowed the sunglasses in her Guinness coloured bob. ‘Give, lady. Who’s the lad? Where’s he from? What the freak’s he playing at?’

Wrinkles blithely curled a crimped lip. Bev moved in close, recoiled at eau de old lady. ‘Listen up, grandma. If that kid jumps . . . on your head be it.’ Rapid blink. Mental cringe. I can’t believe I said that.

‘Yeah, well, that’s one way o’ putting it.’ The flicker of a grin crossed the old girl’s lace-face. Bev’s stunning oratory had won the booby prize: Wrinkles looked as if she was about to share.

Or might have – but for a communal gasp from the crowd. Twenty plus heads angled back. The youth, now standing, teetered precariously, arms flailing, baggy combats flapping. Put Bev in mind of an octopus on heat. Like she’d know. Then a glint from a Zippo lying on the gravel caught her glance, and a pack of Embassy shot overhead. Didn’t take Sherlock. Some joker on the ground must’ve thought Batboy needed a smoke. The lighter had been lobbed first, grabbing for it had almost sent the lad over the edge. When balance was restored, the crowd’s released breath could have powered a wind farm.

‘Knock it on the head you lot,’ Bev yelled. ‘Go and have a word, Danny. You were saying, Mrs . . .?’

‘Parton. Dolly. And ’fore you ask . . . I don’t sing.’

Thank God. ‘And the kid is?’

‘Kevin Skipton. His mates call him Skippy.’ A not helpful image sprang to mind – Bev banished it and focused on Dolly’s words. ‘Lives in one of them maisonettes on the Grove Road? Kev’s the eldest. Lad’s only fifteen, but he looks out for the little ones. Makes sure there’s food on the table, clothes on their backs.’

Yeah. Bet he’s got a tree-house in Sherwood Forest. Bev lifted a sceptical-stroke-cynical eyebrow. ‘Sounds a regular little Robin Hood.’

Dolly shrugged. ‘Okay he thieves a bit, but only to feed the kids. Mind the youngest’s just a bab. Kylie-Anne.’ An indulgent smile faded fast. ‘Sort of crap name’s that?’

‘So.’ Bev joined the dots. ‘The mother’s legged it and Kevin’s cut up? Reckons this’ll get her back?’

‘Summat like that.’

Books. For. Up. Turn. Bev had Batboy pegged as a loser, but not in the family break-up sense. Rough on the lad that. Not that topping himself was any answer. Talk about defeating the object. Empty threat then? On the other hand, if he lost his footing and fell, he’d be more than a crazy, mixed-up kid. He’d be a crazy, mixed up, dead kid.

She looked again at the boy on the roof: the hunched shoulders, pinched features, lank mousy hair and dirt-streaked face. Poor little sod. Most teenagers on the cop-it carried blades, but Skippy carried a cross the size of a cathedral. He’d had to play ma, and presumably pa, to a bunch of snotty-nosed siblings. Skippy’s skinny shoulders weren’t just hunched they were bowed. And his world had come crashing down anyway. God forbid the lad followed.

Bev cleared her throat. ‘Is there a dad in the picture, Mrs Parton?’

‘Be a team photo,’ she sneered. It figured. In this neck of the woods family values were on a par with Aldi price cuts. ‘No,’ the old woman said. ‘The mam’s not much cop – but she’s all they’ve got.’

‘Any idea where she is?’

‘Ain’t you the detective round here?’

*****

Bev did her detecting bit and within minutes patrol cars were en route to half a dozen properties across the city, addresses elicited from Dolly where the errant Sharon Skipton might be shacked up. It wouldn’t take long and no one on site was going anywhere. Least of all Kevin. In between taking and making calls and liaising with Highgate, Bev had shouted up offers of food, drink, a mobile – all in the hope of getting him to open up. Lad had barely opened his mouth let alone his heart.

‘How goes it, boss?’ Mac Tyler. For a guy the size of a grizzly, Bev’s DC was amazingly light on his feet.

‘Whoop-de-do-not.’ She brought him up to speed, asked what had taken him so long.

Mac waggled enigmatic eyebrows, took a warm KitKat from one pocket, an ice-cold coke from another and handed them over with a conspiratorial wink.

‘Ta, mate.’ She took a few glugs, pressed the can against her forehead. The goodies were from the newsagent’s on the corner. Mac wouldn’t have been shopping just for sustenance. ‘And?’ she asked.

‘The lad was banned from going in. Owner says he lifted more stock than a pick-up truck.’

Fitted with the old lady’s story. Bev frowned, glanced round. Where was Dolly?

Mac loosened his collar with a stubby finger. ‘A door at the back’s been forced.’ And he’d had time for a recce. ‘I mentioned it to the rookie. Suggested he keep an eye? The press boys are sniffing round out there.’

‘Tell me about it,’ Bev drawled. The media were chomping at the bit out front, too.

‘How we playing it, boss?’

She’d had a word with the guv. Detective Superintendent Bill Byford wanted a watching brief. No percentage forcing the issue. ‘Softly softly,’ Bev said. ‘No rush, is there?’

And then movement and a flash of colour on the roof caught her glance and everything went into overdrive.

‘Tell me that’s not what I think it is.’ She narrowed her eyes but it was still there.

A baby in a yellow romper suit was being dangled in midair. Kevin Skipton was doing a Wacko Jacko. Was it Kylie-Anne? Kev’s kid sister? The spectators’ buzz descended into sudden absolute silence. Bev’s mind raced as fast as her heart. It was think-on-feet-time.

Then time ran out.

It seemed to happen in slow motion with a soundtrack of gasps and screams. The sickening crunch of the impact, the scarlet splatter and spray. Blood soaking through the tiny yellow jumpsuit. Every horrified gaze was on the crumpled bundle. For what seemed an age no one moved; bodies, expressions frozen in shocked disbelief.

It took Bev several seconds to recognise the smell. Her senses were primed for blood. Not the fumes she was inhaling. Her brain needed a few seconds more to collate the data. Then she scowled, spitting feathers. It was a frigging joke. The baby gear had been wrapped round a doll and a load of paint. The lad must’ve poured it in to something flimsy, a plastic bag maybe. Why the hell…? If the tosser was just having a laugh – she had a damn sight better punch line.

‘Right. You little sod.’ But when she raised her furious gaze to the rooftop, Skippy hadn’t so much flown – as done a runner.

*****

It was more sprint than marathon. The kid must’ve realised he’d not get away. When Bev, breathing hard, arrived at the back of the building, Kevin Skipton was indeed hugging the pavement. Danny Rees, she found out later, had brought him down with a rugby tackle, but it was Dolly Parton’s slipper that was now planted across the lad’s nape.

He gave out a plaintive, muffled, ‘Let me go.’

‘Let me go please.’ Dolly pressed down with her foot.

‘Please!’

‘Never did know when to stop did you, Kevin?’ The old woman released the foothold and turned to Bev. ‘He’s not a bad lad.’

‘Scuse me while I get his knighthood.’ She tapped a Doc Marten on the gravel. Mac ambled over, helped the youth to his feet then frisked him. The only thing Kevin carried was a bit of extra weight.

‘I tried talking him out of it,’ Dolly mumbled.

‘Give, granny.’ Bev chewed her lip; arms folded. ‘Ten seconds. Or you’re both down the nick.’

Blink of an eye and she gave. ‘Ernie Watson was after a decoy. Said Kev could earn himself a bit of pocket money if he created a bit of a stir.’

Bev exchanged glances with Mac. Ernie ‘Tools’ Watson was a small-time villain with a big payroll. He used a lot of kids in the business, made Fagin look like a child protection officer. Ernie had apprentice dealers, carriers, tea-leafs, you name it, all over south Birmingham. The cops had been on his case for a couple of years. ‘Decoy for what? When? Five seconds, lady.’

Dolly gave a resigned sigh. ‘Hold-up at the Eight-till-Late.’

‘And?’

‘Don’t say nothing,’ Kev pleaded. ‘He’ll go ballistic.’

‘Cuff ’em, Mac.” Bev made to leave.

Dolly reached out twiggy fingers. ‘Birches Arcade. Chippie one side, hairdresser’s the other. It’s takings day.’

Not rich pickings then: it was a row of shops on the estate. Still, gift horse, mouth and all that. First things first, though . . .

‘Danny get the cars round there,” Bev ordered. ‘And stand the emergency crews down.’ She glanced at Mac who was already on the phone to Highgate rustling up reinforcements. Hands on hips, she treated Skippy and the old woman to a glare apiece. ‘Decoy I can just about get my head round. But that freaking charade?’

‘Tools come up with the idea,’ Kevin mumbled. ‘I just had to make it convincing.’

‘Don’t hold out for an Oscar, kid. And the sob story?’ Bev glowered at Dolly. ‘That was a load of balls?’

The old woman found her slippers fascinating. ‘It just sort of came out.’

Bev sighed, shook her head. ‘Mac when you’ve finished . . .’ The troops on Sharon Skipton’s trail needed calling off. Waste of frigging time.

‘Kev is good with the kids though. We’re a close family.’

‘Oh, well. That’s all right then.’ Like she meant it. ‘Whose idea was the bloody doll?’ she snapped.

Kevin lifted a tentative hand. ‘Saw that on the box. The Bill? Casualty? Something like that. Looked good didn’t it?’

‘Not as good as your CV’s gonna look, kid. Let’s think . . . breaking and entering, criminal damage, conspiracy, wasting police time, aiding and abetting, perverting the course . . . you getting the picture?’

‘He’ll get a damn good hiding an’ all when I get him home.’

‘Home?’ Bev narrowed her eyes.

‘Shurrup, gran.’ Kevin’s trainer toed the ground; his face was puce.

‘You are joking?’

‘Course I’m his gran. Looking out for him, wasn’t I? I don’t want him getting in trouble.’

‘Glad that worked, Dolly.’ Bev groaned, pictured the paperwork. She was sorely tempted to let him walk. He was only fifteen. No previous. No weapon. No one was dead. He’d likely just get a caution. He wasn’t the sharpest knife in the canteen, but maybe he’d learn a thing or two from this fiasco.

‘Boss.’ Mac slipped his phone in a pocket, beckoned her over. ‘A word.’

She skewered Skippy and his gran with another glare. ‘Don’t move an eyelash. Either of you.’

Mac had just spoken to Danny Rees. It was what you call a partial result. Danny and four other officers had apprehended three goons coming out of the Eight-till-Late. Ernie Watson hadn’t shown, he’d sent his minions, but if Kevin coughed . . .

Bev sauntered across. ‘Okay Skippy. Here’s the deal.’ She didn’t actually say, Spill the beans and save your bacon, but that’s what it came down to. His gran’s hefty two penn’orth plus dire warnings tipped the scales: Tools Watson was no match for the formidable Dolly Parton. Kevin agreed to give a detailed statement later in the afternoon and evidence during the trial.

‘Thanks, officer.’ Dolly tucked her arm affectionately into the boy’s. The warmth seemed genuine on both sides. ‘Come on, love. Let’s get home.’

Bev watched them walk away, chatting and having a laugh. The lad was lucky having Dolly to look out for him, keep him on the straight and narrow. It might all go pear-shaped, but when the case came to court, hopefully Kevin would be in the witness box not the dock.

Job done, sort of, Bev and Mac headed for their motors. She kicked a stone, apparently deep in thought.

‘Okay, boss?’

‘Nah.’ She sniffed. ‘Well pissed off.’

‘Why’s that?’ He tugged a ring pull on a can of Red Bull.

‘Missed a great line, didn’t I?’

‘Yeah?’

‘Hawaii Five-o? Rees the rookie?’ She flashed a grin. ‘Never got to say: book ’em, Danno.’

‘Lucky that. His name’s Danny.’

‘Pedant.’

Loved this – absolutely vintage Maureen Carter. Sharp, well-observed, and pitch perfect for the marvellous character, Bev Morriss.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Sarah. Glad you like it . . .

LikeLike